The Foundational Image: On Cinèma Pur

The moving image, in its earliest days, assumed a rudimentary form of single-shot, several-second-long accounts of everyday life. These vignettes were popularised in-part by the Lumiére brothers’ invention of the Cinematograph. Etched deep into our collective subconsciouses are the snippets of 19th century urban life in Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895), Snowball Fight (1897), and The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896); the latter of which legendary for supposedly causing a sudden mass-exodus of the Parisian bourgeoisie at its inaugural screening, with the unsuspecting onlookers fearing that the oncoming train would rip through projector-screen and bundle straight into the auditorium.

[]

{But whilst the Lumieres paraded their cinematograph around Paris}, the boundaries of this new visual medium was about to be pushed beyond merely the realm of documentation. In the hands of George Mèliès, even the most ordinary street scene could prove transformational.

The story goes as follows; Méliès, who had attended the Lumières’ exhibition in boulevard des Capucines earlier that year, was busy capturing the bustle of a Parisian high-street. In the process, his camera jammed, forcing him to stop shooting momentarily to fix the defect. After Mèliès developed and watched the footage later on, he noticed something astonishing: the people in the image, whilst walking along the street, had been suddenly and inexplicably replaced by a horse-drawn carriage.

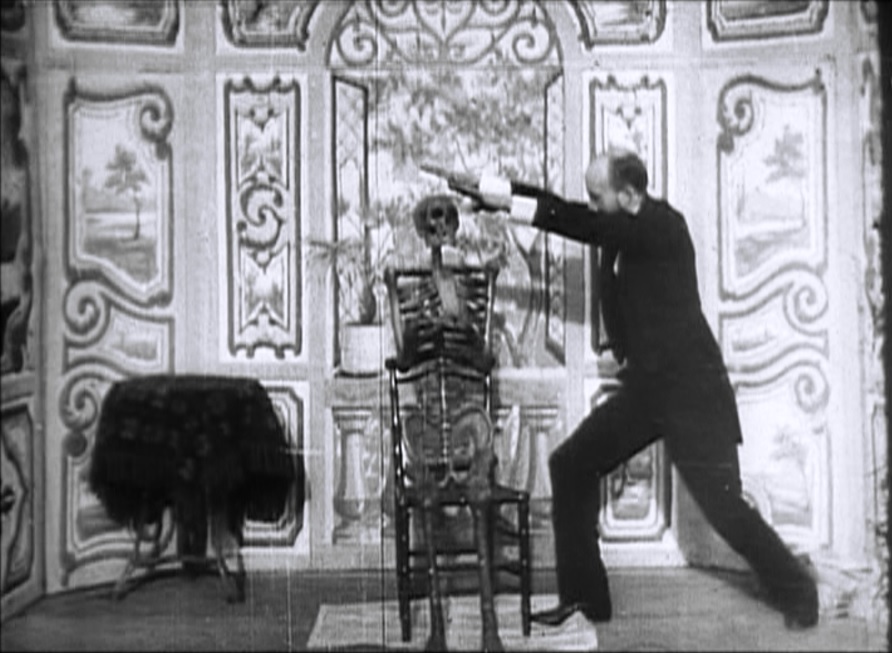

This event, if true, marks what is possibly the most consequential inflection point in cinematic history. Visual artists, only recently given the ability to take time captive, now held the tools necessary to manipulate it to their will. Mèliès, the adventitious creator of the phenomenon, used the revelation to bring existing theatrical illusions to the silver screen. His earliest surviving work, Escamotage d’une dame chez Robert-Houdin (1896), is one of the first examples of the ‘jump cut’, a menial technique by today’s standards, but periodically revolutionary for its ability to suddenly change the contents of a frame, if executed correctly.

Whilst the fledgling art of cinema was almost unanimously heading in the direction of strict narrative structure and adherence to newly defined industry formalities, a small subset of artists took exception to the idea that their new, radical and beloved art-form was to be beholden to conventions of more established disciplines such as theatre, literature and painting. This [fragment of filmmakers] viewed the motion picture as an entirely novel medium, and as such strived to

Early on in the evolution of the moving image, formal conventions arose as a way to restrain a film to a singular, cohesive narrative.